Okay, “neurodiverse” or “neurodivergent” is an adjective you’ve probably heard used to describe high-functioning people on the autism spectrum, but how does it apply to kids with fetal alcohol disorders? Aren’t these completely different phenomena? Is there any good reason for expanding the use of this term?

The word “neurodiversity” first started to be used in 1998 and, yes, the context was at first was limited to an activism promoting the rights and sense of self of people on the autism spectrum. 1

More recently, though, because of a growing general awareness of what it means to live with an autism spectrum disorder, people living with other sorts of brain-based differences have begun to push for a similar degree of societal recognition.

So, let’s consider all the people who deal in their daily existence with the effects of prenatal exposure to alcohol — in what ways are they “neurodiverse”?

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders are brain-based disabilities. The causes are anthropogenic, you could say, rather than congenital. But FASDs are life-long, there are no cures, and no one facing such challenges asked to be born this way.

People with a fetal alcohol disorder are not typical in the way their brains work. In fact, there is a great deal of behavioural and neurological overlap between FASDs and other neurodevelopmental disorders including autism spectrum, Tourette’s, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), sensory integration disorder, and — maybe most of all — developmental trauma.

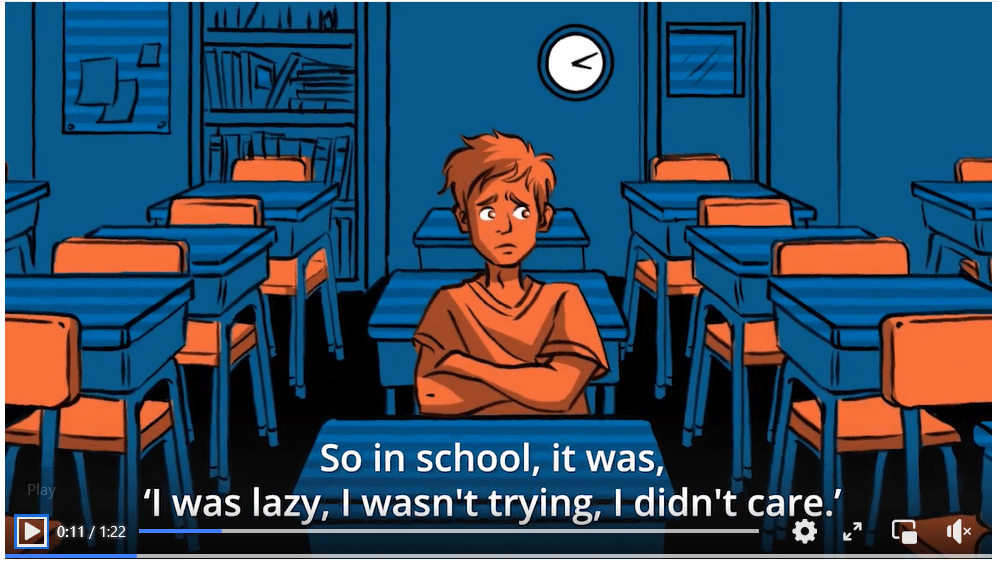

Yet the characteristic traits may not be immediately perceptible to anyone unfamiliar with the disorder. Impulse control, emotional regulation, the ability to read interpersonal cues and body language — all of these neurological functions may be affected. When teachers, school officials, police officers and others are uninformed about what an FASD does to a brain, they tend to make punitive moral judgments regarding what can appear like non-compliant behaviour (as in the cartoon reproduced above: “he’s lazy,” “he’s not trying,” “he doesn’t care”).

Speaking of acronyms and clinical nomenclature, by the way, no person with a brain affected by prenatal exposure ever asked to be labelled with an ugly-sounding and inaccurate acronym all of their lives! 2 Myles Himmelreich, with the advocacy group Changemakers (he is the one represented as a comics everyman in the animated video I’ve taken the still image from above), likes to push back by saying that FASD really stands for “Faith, Ability, Strength, Determination.” 3

As a parent of a kid diagnosed with an FASD, I’ve taken a few years myself to come round to “neurodiversity,” but I now believe it’s the key concept if children with complicated histories of developmental trauma are to be understood, included, and supported in our communities.

To get a sense of what’s at stake, we might ask, “neurodiverse” as opposed to what? Not very long ago at all — think the late 1990s — we would have just said “permanently brain-damaged.” That term is both harsh and medically accurate. So . . . are we merely indulging in a euphemism to say instead that a person living with an fetal alcohol disorder is neurodiverse?

Far from it. This nomenclature is more than just gauze to cover over a troubling reality, or to protect the over-sensitive. A changed language can transform self-understanding as well as alter the perceptions of others. A changed language has the power — as the precedent of autism activism shows — to make something happen in the world. A changed language matters, for people living with these disorders, for their families and those who love them, for society at large.

The use of a term like “neurodiverse” acknowledges that people living with FASDs have strengths and talents as well as what the clinical world calls “deficits.”

The irony is that while a large academic industry has grown up the last fifty years around fetal alcohol disorders and a vast amount of research has been carried out, improving the experts’ capacity to diagnose — a good thing, certainly! — and proving beyond all doubt the range of harms that alcohol does to a baby in utero, all of these abstract scientific findings have not yet made much difference to the difficult lives of the millions of North Americans who live with FASDs. All that scientific knowledge, in other words, is not making it out into the world.

Why not? It’s a ten billion dollar question in urgent need of an answer. All I know is that, at present, the aggregation of data seems only to magnify the shame piled unfairly upon mothers with addictions; society continues its heedless love affair with alcohol; and virtually no one wants to hear about what it would mean to stay with, to stay with and tame, this collective — not individual — trouble. 4

The “deficits” approach, if anything, has intensified the stigmatizing of the people and families and caregivers who live with the condition. The result is that fetal alcohol spectrum disorders have become socially unmentionable despite the fact that their prevalence is even greater than that of autism spectrum disorders. The support and slowly spreading understanding one would expect to find in Canadian schools in 2023 is — with a few remarkable exceptions [see my blog post of Jan. 26, “Two Films, Twenty Years”] — almost everywhere absent. Instead, the bitter truth is that our justice and correctional systems are the institutions that now demonstrate the greatest understanding of people who live with FASDs. 5

Perhaps it is time to speak, then, about how people living with this disability belong, in their neurodiversity, to the human family. About how they too have talents, gifts, and generosities of spirit that can be unfolded over the years. It is time to broaden the conversation about what these neurodiverse children and adults have to offer everyone else — and about everything we owe them too.

People with a fetal alcohol spectrum disorder have the potential to learn and develop as human beings. They share in the inalienable human right to an education — to finish high school, and to go further if they are able. They have a right to be included in our communities — and to be supported in their lives.

Just like those on the autism spectrum, most children with an FASD will need special accommodations in school: modified classrooms, shortened school days, and highly trained teachers who understand the relation between the brain and challenging behaviour. 6 Sticking such kids in “behavioural” classes without careful attention to how brain and environment are interacting in those classrooms is a recipe for the worst possible outcomes.

Using a term such as “neurodiverse” meshes with the argument that the ways of being of people with fetal alcohol disorders are best understood and supported by social rather than medical models of disability. That is, an FASD-affected brain is not ever going to be neurotypical; no ingenious apportioning of medications will magically make everything right. But social environments can be modified — above all by informing other people about the realities of the disorder — and modified in ways that will significantly improve the quality of life for many people.

Finally, let’s be clear that acknowledging the strengths and potential contributions of people living with FASDs in no way precludes or undercuts the vital work of preventing prenatal exposure. That work calls for many more people, everywhere in the world, to be educated about the dangers of even moderate alcohol consumption during pregnancy.

But in the same way that we can accept and support the differences of those who live with autism now and look ahead to a time when there may be genetic therapies for the disorder (especially in its severe forms), we should be able to accept and support the differences of those who live with FASD now and look ahead to a day when economic injustice, violence, and intergenerational trauma will be so reduced that no unborn child will be exposed to the ravages of alcohol.

—————————————————————————————–

1 The Oxford English Dictionary cites a 1998 online forum as its first recorded instance of “neurodiversity.” Sociologist Judith Singer used the term “neurological diversity” in an academic paper from 1998; and journalist Harvey Blume used the word “neurodiversity” in “Neurodiversity: On the Neurological Underpinnings of Geekdom,” “published in The Atlantic in 1998. (See the position paper by Kelly Harding et al., “Neurodiversity and FASD,” Canada FASD Research Network, Feb. 2023.)

2 Inaccurate in its first word, “fetal,” which suggests that the dangers of prenatal alcohol exposure begin only after the eighth week of development, when in fact the effects of alcohol during the embryonic period — weeks three to eight — are even greater than they are during the fetal period. (Personal communication, Dr. Emily Rusnak.)

3 See CBC Radio, White Coat, Black Art, March 29, 2019. <https://www.cbc.ca/radio/whitecoat/you-re-weird-you-re-different-and-nobody-wants-to-be-your-friend-the-loneliness-of-fasd-1.5075121>

4 “Staying with the trouble” is Donna Haraway’s book title about the disordering effect of environmental crisis. The guarded optimism that comes with neither burying one’s head in the sand and pretending there is no problem nor wishing to be elsewhere than in an earthly present but instead facing up to the trouble and acknowledging that there can only be long-term healing seems the right attitude to take with fetal alcohol disorders too.

5 For example, see the statement made by Howard Sapers, Correctional Investigator of Canada, to a 2015 Parliamentary Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights that considered legislation to limit harsh sentencing for offenders diagnosed with a fetal alcohol disorder (https://openparliament.ca/committees/justice/41-2/67/dr-gail-andrew-1/?page=1); or the federal Department of Justice document called “Exploring the Use of Restorative Justice Practices with Adult Offenders with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder” (https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/jr/efasd-etcaf/p1.html). Kudos to the progressive-minded individuals in these institutions. But, as Sapers told Parliament in 2015, it would be far better “to have in place upstream diversion and treatment programs, services and supports in the community” before people with FASDs get involved with the justice system.

6 Diane Malbin (author of Trying Differently, Not Harder) is the innovator of the “neurobehavioral” approach to caring for children with fetal alcohol disorders. It is hard at the best of times to parent a child with an FASD; without Malbin’s insights, I can attest that it would be next to impossible. For recent research into the efficacy of the neurobehavioural approach, see Christie Petrenko et al, “A Mobile Health Intervention for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (Families Moving Forward Connect): Development and Qualitative Evaluation of Design and Functionalities,” JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020 (8: 4) e14721. The Families Moving Forward program, at the Seattle Children’s Hospital, follows the neurobehavioral model. See https://familiesmovingforwardprogram.org/?page_id=1919