Towards the end of my last post, I wrote these sentences: “Kids with a fetal alcohol spectrum disorder aren’t ‘born broken,’ but they are born with some of the crucial neurological connections incomplete, and hence if they are going to thrive in the world they will need to fit, and be fitted, consciously and intentionally, into a web of social interdependency that begins with their family and rays out into the surrounding community. Without such a web of supports, without a collective awareness of what kids and youth with FASDs need over the long term, disaster awaits. This is not hyperbole.”

No, not hyperbole. To get a sense of just how grave the situation is for children and youth with a fetal alcohol disorder when that web of supports is absent, all you need to do is read, as I did recently, through the Investigative Reports that Alberta’s Child and Youth Advocate is legally required to produce and publish after the death of any young person “receiving services” from the province’s (recently renamed) Seniors, Community, and Social Services ministry.

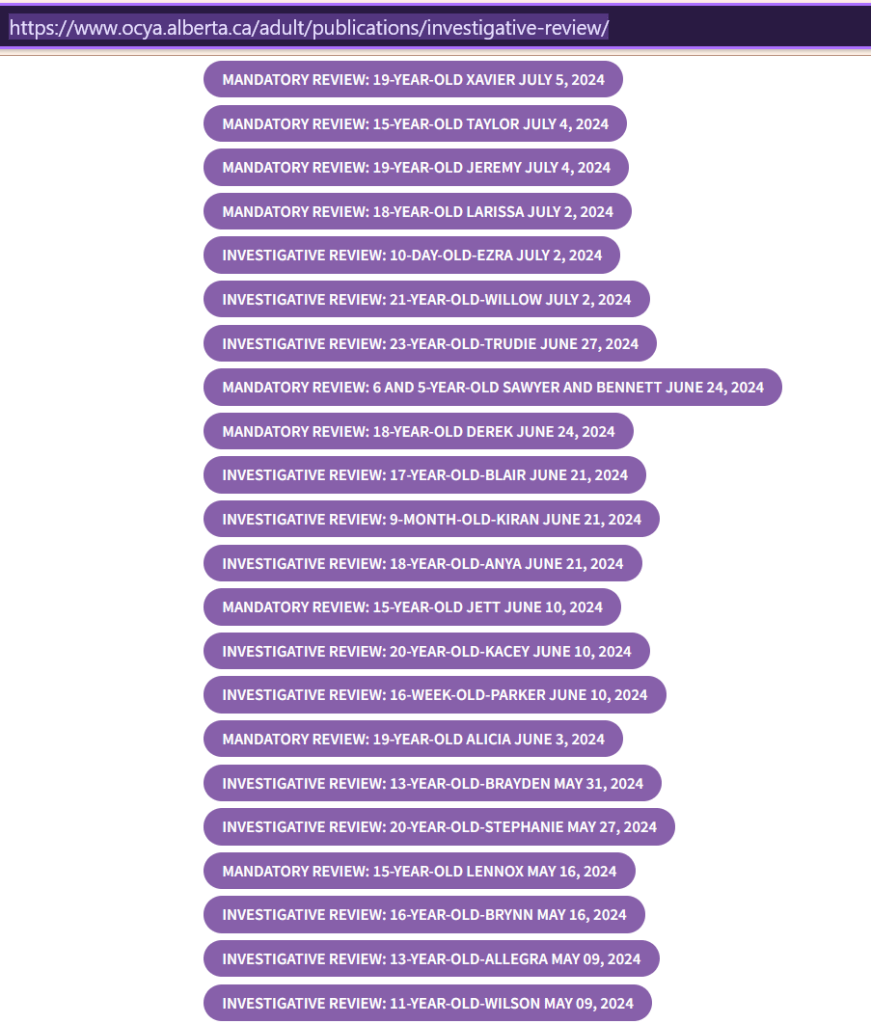

The Office of the Child and Youth Advocate, between late September 2023 and early September 2024, published on its website (https://www.ocya.alberta.ca/adult/publications/investigative-review/) eighty-seven investigative reports. These are reports into the circumstances of “the death of a young person involved with the Child Intervention system [when that person’s death] meets the criteria for a mandatory review as required by the Child and Youth Advocate Act (CYAA).”

The current Child and Youth Advocate is Terri Pelton. Her office’s reports must be published within 365 days of the death of any child or youth who was receiving child intervention services up to two years before their passing. Hence the ages of these young people range from — at the youngest — a few days or weeks up to — at the oldest — the very early twenties.

All but four of the reports tell of the deaths of individual children or youth. That is, by my count, 84 deaths between September 2022 and September 2023. (All names used in the reports, by the way, are pseudonyms.)

I can’t imagine many people in this province have perused these eighty-seven reports other than Ms. Pelton and her staff. Reading through them is dispiriting and demoralizing — emotionally heavy work. I think of two literary stories that hinge (though differently) upon moral witness: Herman Melville’s famous fictional character Bartleby the Scrivener; also of Ursula K. Le Guin’s parable, “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” 1

Ms. Pelton’s reports, that is, bear witness to something that cannot be lost sight of if a fundamental decency is to live on in the public life of this Canadian province. Writing them must have been disturbing and exhausting. Before I say anything, then, let me praise the work of Ms. Pelton and her staffers. It is vitally important that these reports have been produced and made available online.

Prior to 2013, the circumstances of deaths of children and youth in care were kept secret (i.e., “private”) by the provincial government. 2 Since 2013, the office of the Child and Youth Advocate posted on its website the occasional mandatory report, but nowhere near as many have been published in its brief institutional existence as have appeared over the last year under Ms. Pelton’s tenure. (Between 2018 and 2022, for comparison, the OCYA published only fourteen such reports. 3) The result is a very significant increase in information available to the public about the workings of the child protection system in Alberta.

According to the boilerplate at the beginning of every report, “investigative reviews are designed to improve the lives of young people by identifying ways to enhance services and supports, leading to system improvements and better outcomes for young people and their families.” I don’t doubt that everybody involved would like to see improvement. But can we cut through the paralyzing language of bureaucracy and find a way towards real improvement? A first step would be to nerve ourselves to read these reports and reflect on them.

I once had strong opinions about such matters as foster care vs. kinship care vs adoption, the over-representation of Indigenous children in the system, and so on. But my opinions have mostly fallen away over a dozen of years of nothing getting better — of things getting worse, in fact. It’s not that these complexities aren’t in the background of Canada’s child protection systems. They are.

Nor would I want to downplay the magnitude of the toxic drug crisis in Alberta — the horrific degree to which fentanyl (often combined in a poisonous cocktail with methamphetamines) has become a killer of children and youth — and adults — trapped in adverse circumstances. More than a third of the deaths documented in these recent 2023-24 reports are the immediate result of overdoses.

But there is something else of crucial importance that is not getting enough notice anywhere — not in Ms. Pelton’s office’s analyses, not in the occasional media piece on her office’s reports, and certainly not from provincial officials.

This is the pattern related to fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. As I will show, it is present in more than half of the OCYA’s most recent investigative reports.

Fetal alcohol disorders a factor in dozens of child & youth deaths in 2022-23

I read through 87 investigative and mandatory reports, published between September 20, 2023 and September 6, 2024, which tell about serious and fatal incidents involving 89 children and youth between 2022 and 2023. (One report is about two siblings both involved in the same car accident; another is about two siblings who both perished in a house fire.) Eighty-four of these children died. Thirty-five out of eighty-four deaths were the direct result of drug overdoses or poisonings, and most of these a combination of fentanyl and methamphetamine.

Fifteen of the eighty-two children and youth — 19-year-old Alicia; 20-year-old Stephanie; 19-year-old Hugh; 15-year-old Riley; 21-year-old Lennie; 15-year-old Farah; 19-year-old Arlo; 15-year-old Mira; 14-year-old Karey; 15-year-old Aleda; 15-year-old Mackenzie; 12-year-old Gill; 18-year-old Crystal; 19-year-old Gavin; and 20-year-old Timothy — were diagnosed at some point in their lives with a fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Another two — 15-year-old Jeffrey; 11-year-old Wilson — were raised in biological families where either a sibling or a parent had been diagnosed with an FASD.

In the cases of twelve more children and youth — 19-year-old Xavier; 19-year-old Jeremy; 23-year-old Trudie; 18-year-old Derek; 18-year-old Ashlyn; 22-year-old Cheyanne; 21-year-old Kelvin; 20-year-old Aden; 17-year-old Jonas; 11-year-old Rowan; 19-year-old Bree; 18-year-old Jenika — the Child and Youth Advocate’s reports note that fetal alcohol spectrum disorder was identified as likely by workers or teachers or medical professionals but that the concern was never followed up on / no assessment occurred, so no diagnosis was made.

Another eighteen children and youth, fourteen probable — 18-year-old Larissa; 17-year-old Blair; 14-year-old Kacey; 13-year-old Brayden; 15-year-old Lennox; 18-year-old Carolyn; 18-year-old Bonita; 17-year-old Henley; 14-year-old Caden; 16-year-old Avery; 17-year-old Kali; 19-year-old Nadie; 18-year-old Hannah; 15-year-old Hunter — and four possible — 5-year-old Quinn; 8-year-old Max and 7-year-old Naomie; 15-year-old Melody — manifested some of the signs and symptoms of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, but these signs were apparently not recognized by any of the workers, teachers, and medical professionals involved in their lives.

That is, there is no mention at all of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder in the investigative reports for these 18 children and youth, even though Alberta’s psychologists and psychiatrists devised in their cases (and those of the 27 mentioned above) a remarkable array of throw-it-at-the-wall-and-see-if-it-sticks diagnoses including “conduct disorder,” “oppositional defiance disorder,” “adjustment disorder,” “neurobehavioural disorder,” “emotional/behavioural disorder,” “emotional and behavioural disability,” “disruptive behaviour disorder,” “pathological demand avoidance disorder,” “generalized anxiety disorder,” “panic disorder,” and “disruptive mood disregulation disorder.” (More about these diagnoses below.)

In total, that is, of the 89 children and youth whose lives are reviewed in the investigative reports that I read through, 47 — or 52.8% — involved children or youth with a diagnosed, probable, or possible fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. And 45 of those children and youth with an FASD, let me say again, died.

Observations and reflections

First, caveats and provisos. All of these children and youth come out of complex circumstances, some of which are adverse, and none of those circumstances are exactly alike. All have been touched by trauma; and trauma can cause injury to the brain whose effects are difficult to distinguish from those of prenatal alcohol exposure. Moreover, there are certainly other commonalities that one could take up in an effort to understand what went wrong. 4

By highlighting the pattern discernible in these reports related to fetal alcohol disorders, I do not mean to assign blame to the individual biological parents or families of these children and youth. The abuse of alcohol is a social determinant of health. A corollary: Canadian society has a continuing problem with alcohol. But equally, I do not mean to let the experts and the industry professionals off the hook either. That is, a fetal alcohol disorder diagnosis is not and should not be a death sentence. If more than forty children and youth in the care of the Alberta government with an autism diagnosis were to perish in a single year from over-dose, suicide, and street violence, there would be outrage (and rightly so).

Also: fetal alcohol spectrum disorder is indeed a spectrum. No child or adult with an FASD has exactly the same brain characteristics / abilities / disabilities as any other. Not only that, but the home environment is just as important for kids with an FASD as for every other growing human being. The more insecure, abusive, violent, unloving, neglectful a home environment, the more “adverse” the developmental trajectory. And the opposite, of course, is true as well.

While generalizations will never line up perfectly with individual situations, it is nevertheless safe to say that these are the challenges that many children and youth with a fetal alcohol disorder live with: high levels of anxiety; impaired capacity to regulate their emotions; vulnerability to sensory overload (e.g., loud noises); impulsivity (including impulsive aggression); impaired short term memory and/or auditory processing; emotional and intellectual dysmaturity (e.g., a 15-year-old may manifest, at times, the judgement and emotional self-regulatory capacity of someone half their age); poor “adaptive functioning” (i.e., capacity to read body language and gauge spatial cues); various ADHD-like qualities (e.g., inability to sit still; high energy; trouble paying attention except for short periods).

Yet, reading through the 44 reports I pick out above in which fetal alcohol disorders have a prominent role, it becomes apparent that many or even most of the families (biological and kinship / foster), support workers, medical practitioners, and teachers / educational aides / school administrators involved did not recognize or understand the unique brain-based challenges these kids faced or grasp the accommodations and community supports that would be needed over the long term. Instead, the reports document, over and over, adult impatience and exhaustion at unexpectedly difficult “behaviour” and socially unacceptable “conduct.” 5 And, then, at a tragically predictable point in their life histories — usually around the time child turns into youth — a heavy institutional hand comes down on these kids, with consistently disastrous results.

Basic principles — with some examples of where things can go wrong

But caregivers and support workers should not be so surprised. Once we know a child has an FASD, there are a number of basic principles that should guide caregivers, support workers, medical practioners, educators. These principles are bound up with the brain-based characteristics I list above that are most typical among children and adults with fetal alcohol disorders.

1. Fetal alcohol disorders are common in the general population, and much more common than that among children and youth in care. 6 Yet it’s very easy — for experts — to mistake the various symptomatic behaviours of this neuro-developmental disorder for other things. Hence screening is crucial for all kids in the care system, followed-up by full and accurate diagnosis when appropriate. These sentences, found in the reports on the second group of children and youth that I draw attention to above, are all too typical:

When Xavier was 11 years old, he physically acted out, did not follow the rules, and left his

placement without permission. He had a contract at school to help him focus and manage

his behaviours. … Caseworkers and school staff discussed having him assessed for fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), but it was not arranged. Xavier had two subsequent placements over the following year where caregivers struggled to manage his escalating behaviours.

Jeremy’s physical outbursts intensified, and [his foster mother] found it increasingly difficult to manage them. She requested an assessment for Jeremy, and at different times, caseworkers noted that he required a fetal alcohol spectrum disorder assessment, but these assessments were not pursued. He was referred to a play therapist who saw him regularly and provided parenting strategies for his caregivers.

At 14 years old, [Trudie] was assessed for fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. A diagnosis was not confirmed, and counselling was [instead] recommended to address her feelings of abandonment, self-worth, and anxiety about the future. When Trudie was 13 years old, [her kinship carers] asked that Trudie … be moved because they could not meet [her] escalating needs. It is unclear if supports were provided to maintain the placement. Trudie [was] subsequently moved to group care.

Derek continued to have difficulty in school and was frequently suspended for verbal and

physical outbursts. Teachers felt he needed a full-time aide, but there was a disagreement

between Education and Child Intervention staff about funding, so it was not provided.

At 11 years old, Derek began to use substances and self-harm, and [his kinship carer] asked for a fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) assessment, but it was not pursued. He lived

with her for approximately eight months when she became overwhelmed and could not

meet his needs.

When Ashlyn was 11 years old, she completed a FASD assessment that found she had low

average cognitive functioning and a learning disability in math. While she did not meet

the full diagnostic criteria for a neurobehavioural disorder or FASD diagnoses, she would

require life-long support to address impulsivity and to help with organizational skills. … [She] started seeing a psychologist to address her grief and loss, self-esteem, and mood issues. She was prescribed medication to help her focus.

After [Cheyanne’s biological mother] was released from jail, she started having gradual contact with six-year-old Cheyanne. She told caseworkers that she used alcohol during her pregnancy; this information was not shared with Cheyanne’s caregiver, pediatrician, nor school staff. [Her long-term foster mother] suspected that Cheyanne had fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) and asked for her to be assessed; it is unclear if this happened. … [Fifteen-year-old] Cheyanne had [Individual Placement Programs] in high school, but the level of support changed. She was enrolled in regular classes and no longer had one-on-one help. It was her responsibility to ask for additional support when needed, which she struggled to do. Throughout the school year, her grades and attendance declined. School staff noted that she often appeared depressed and connected her with a school counsellor. Cheyanne pulled the fire alarm at school and was charged. She completed extrajudicial sanctions. School staff asked for a psycho-educational assessment. It does not appear to have been completed. 7

All of these young people grew up in complex adverse circumstances; all faced developmental trauma and loss as well as the effects of prenatal exposure. My point here is not to suggest that a diagnosis of a fetal alcohol disorder would have turned their life changes completely around or rewritten their story. But a proper diagnosis would have given their caregivers a fighting chance at getting these children getting the supports and accommodations they needed.

Take Cheyanne’s story, for example, a particularly sad one. In the years after her diagnosis was buried by caseworkers, her long-term foster mother adopted her — but, lacking this crucial piece of information, the placement was troubled and eventually broke down. By high school, Cheyanne was receiving no extra support at all — in fact, she was expected to arrange for that support herself! — and was even criminally charged by the school when she pulled a fire alarm one day. Should the administrators of any 21st century Canadian school feel justified in applying the full weight of the justice system to a 16-year-old with a brain injury characterized by impulsivity and impaired executive functioning? This happened to a girl named Cheyanne somewhere in Alberta in 2017 or 2018. Ms. Pelton’s office’s reports give me good reason to fear that a number of incidents very much like it will be recurring somewhere else in our province in the coming year as well.

2. Psychologists and psychiatrists shouldn’t be bending their diagnoses into strange shapes (“pathological demand avoidance disorder,” “disruptive mood disregulation disorder,” “generalized anxiety disorder,” “oppositional defiance disorder”) when the obvious answer is staring them in the eye. Avoiding the diagnosis of FASD because of good intentions rather than professional incompetence — as seems possible in a number of the diagnoses noted in Pelton’s reports — doesn’t cut it either. Yes, there is ugly social stigma associated with fetal alcohol disorders, but, let us be clear, it is far, far worse to suffer from the disability and to be both unaware of it of yourself and to have foreclosed by harsh moralistic judgments the possibility of receiving compassion and understanding from those around you.

3. People who live with fetal alcohol disorders live with anxiety. Anxiety is the substrate beneath their impulsivity and distractibility, their emotional volatility, their challenges with self-regulation, and their quickness to fright and overwhelm (and so, sometimes, in some circumstances, to impulsive aggression). Hence these children and youth need a secure, loving home environment more than anything else. If they lose that kind of environment, they are even more inclined than most to depression and mental illness, and so to self-medicate with street drugs. (As the Child and Youth Advocate’s reports show, suicide is the named cause of death of six of these children and youth, in addition to the thirty-one overdose deaths.) Timely access to FASD- and trauma- informed therapeutic services is crucial, but most of all an awareness among carers and support workers how the mental health vulnerability and the risks of social exclusion can be mutually reinforcing.

4. A common feature of life with fetal alcohol disorder is dysmaturity. That is, a sixteen-year-old may have the emotional maturity of someone half their age. A twenty-one-year-old may be more like an ten year-old in judgment. Dysmaturity combined with impulsivity and impairments in adaptive functioning (e.g., reading social cues and body language) means that teenagers living with an FASD are unusually susceptible to being negatively influenced by the ‘wrong crowd.’ A group home is a very dangerous place for such a young person. It is essentially a conduit to the street and to the poisoned drugs sold there.

To give an example from one of the investigative reports: it hard to see why informed child protection workers would have moved Karey, who had a diagnosis of FASD, when she was thirteen from a foster placement into a group home:

Karey was put on new medication; she was often angry, and her anxiety and hallucinations increased. [Her foster parents] were concerned for the safety of the other children in their home. They were not sure how to help Karey and wanted her to have the support she needed; she was subsequently moved to a group home. … At 13 years old, Karey functioned at the level of a 7-year-old child. She was easily influenced by her peers and was not able to fully understand or predict consequences. Within weeks of moving to the group home, Karey was introduced to drugs and was sexually exploited. She left her placement to use substances, and while unsupervised, she was assaulted multiple times. 8

Within a year Karey was found “deceased in the community” (i.e., on the street), with police suspecting the toxic drug supply caused her death.

It needn’t be this way — educate, advocate, diagnose, accommodate!

For anyone reading this who cares for or works with kids who live with complex trauma, please don’t get me wrong — I’m am as far as possible from saying that it’s a piece of cake to look out for children or youth with FASDs. On the contrary. I have a twelve-year-old daughter with this diagnosis and caring for her, keeping her safe over the long term, has demanded more of me than anything else so far in my life. Every parent or caregiver comes to realize at some point that no one can do it alone without burning out. No one can be endlessly patient, infinitely compassionate forever. We have to spell each other off. Only a community of support can have long-term success in nurturing such kids.

But as we slowly work towards building up that web of support and care, there must be much more that can be done to prevent our children and young people dying so miserably on the streets in such appalling numbers. I hear at present from Alberta’s bureaucrats and politicians and academic experts only a resounding silence. Silence both about all of these needless deaths; and silence as well about the interlocking causes behind them.

Let’s talk about it at least.

—–

1 Source of the AI-generated “Omelas” image at top of page: <http://hliwwa.deviantart.com/art/Omelas-Concept-art-134303519>

2 The “Fatal Care” investigative journalism series of 2013 in The Edmonton Journal and the Calgary Herald caused a stir — and led to an inquiry — by first revealing preliminary numbers of children and youth who had died in the care of the province between 1999 and 2013. That first (inaccurate) count was 145 deaths. (<https://edmontonjournal.com/news/edmonton/alberta/fatal-care-about-this-series>) In January 2014, the government of Alberta released a much higher number for 1999-2013, which included youth over 18 who had at one time received services from the Human [i.e., Social] Services ministry as well as younger children who were “known to” the ministry. That total was 741 deaths. <http://www.humanservices.alberta.ca/documents/deaths-of-children-known-to-Human-Services-1999-2013.pdf> But it should be noted that the numbers from 2022-23 investigated by Ms. Pelton’s office are a lot higher than they were a decade ago: eighty deaths in the most recent documented year compared to an average of about fifty-three deaths a year over those fourteen years (1999-2013).

3 See <https://www.ocya.alberta.ca/adult/publications/investigative-reviews-2018-2022/>

4 Most of these children and youth are Indigenous, for instance. For many commentators, that will always be the most salient fact about these cases. My analysis intentionally does not take up that commonality for the reason that I believe an exclusive focus on ethnicity works to obscure the extremely high prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder among all children involved with the province’s child protection system. Also, to be clear, in my view, every one of the OCYA’s investigative 2023-24 reports details a situation (or situations) that at one point or another justified the deployment of child protection services. It is almost entirely in the follow-through that the dysfunction of the system becomes apparent.

5 See the report for 18-year-old Crystal (who died of suicide). She had been doing reasonably well with a foster family, going to elementary school and liking it. Then at age 13, “[her foster parents] said that they were frustrated with … Crystal because they argued, she did not tell the truth, and she took things without permission.” Soon afterwards, her foster parents asked Crystal to be moved from their home, even though they had cared for her for ten years. Things went badly downhill for Crystal in the following years. But we should note that behaviours such as lying / stealing / arguing are very common among kids with fetal alcohol disorders and trauma; they are brain-based, not indicators of moral character; and there are ways to work with such behaviours. It appears workers and foster parents are not being taught to anticipate how FASD is likely to manifest in families’ lives.

6 The most conservative estimate of prevalence – nine per 1,000 – was a number used by Health Canada in 2006. But a widely cited 2018 study by Svetlana Popova et al. of elementary school students (seven through nine years of age) in the Greater Toronto Area estimated a prevalence rate of two to three per cent in this metropolitan population (2). And as of 2024, the Alberta government’s own dedicated web-page estimates a 4% prevalence of FASDs among the general population, or “approximately 174,000 Albertans.” (https://www.alberta.ca/fasd-in-alberta.aspx#jumplinks-1). A study by Lange et al., in “Prevalence of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders in Child Care Settings: A Meta-analysis,” Pediatrics October 2013, 132 (4) e980-e995, calculated the “overall pooled prevalence” of FASDs “among children and youth in the care of a child-care system” to be 16.9%. This latter number seems extremely conservative to me. See my related observations about the frequent failure of diagnosis as documented in the OCYA’s 2023-24 investigative reports.

7 Italics are my additions. See <https://www.ocya.alberta.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/MandRev_19-Year-Old-Xavier_2024July5.pdf> <https://www.ocya.alberta.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/MandRev_19-Year-Old-Jeremy_2024July4.pdf> <https://www.ocya.alberta.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/InvRev_23-Year-Old-Trudie_2024June27.pdf> <https://www.ocya.alberta.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/MandRev_18-Year-Old-Derek_2024June24.pdf> <https://www.ocya.alberta.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/MandRev_18-Year-Old-Ashlyn_2024Apr15.pdf> <https://www.ocya.alberta.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/InvRev_22-Year-Old-Cheyanne_2024Mar28.pdf>.

8 <https://www.ocya.alberta.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/MandRev_14-Year-Old-Karey_2023Dec18.pdf>

One response to “Reflections on the Alberta Child and Youth Advocate’s 2023-2024 Investigative Reports into the Deaths of Children and Youth in Care”

Indeed. Thanks for the incisive analysis, Mark.

LikeLike